Columbia University Pupin Hall

Pupin Hall, Columbia University.

Photo: Frank da Cruz, April 2002

| |

Rutherford observatory has been in continuous operation since Pupin was constructed, but in 2009 a new "Northwest Corner Building" was erected next to it, six floors higher than the roof of Pupin and blocking a significant portion of its field of view, and (when it opens) no doubt also putting out a considerable amount of light, obscuring the remaining open sky. The Astronomy Department, which still exists, is seeking a new home for the instruments. HERE is a link to a Spectator article on the subject, 1 October 2009, for as long as it lasts.

The Manhattan Project

Pupin Hall is also where Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilard, and other physicists began work on developing a self-sustaining neutron chain reaction in 1939, in the basement (five levels below the entrance shown at the bottom of the photo the photo; until about 1970 when the new gym was built, the lower four floors were exposed and Pupin was fronted by grass and trees). When Fermi's work moved to the University of Chicago after Pearl Harbor (so it would be safer from attack from the Atlantic), it was called the Manhattan Project because of where it had begun, and it kept its name when it moved later to Los Alamos, New Mexico.Professor Eckert's Astronomical Computing Bureau stayed behind in Pupin to perform war-related computations, such as ballistic trajectories, while Professor Eckert himself directed the Nautical Almanac office of the US Naval Observatory for the duration of the war. Uranium separation and heavy water production research were carried on in the basement of Pupin, where to this day radioactive equipment such as the cyclotron's 3-ton cobalt-steel electromagnet remains stored in a locked area (other parts were moved to the Smithsonian Institution in 1965 when the cyclotron was shut down). The uranium separation work (development of the gaseous diffusion technique) of Columbia's Special Alloy Materials (SAM) Laboratories [sorry, link defunct] expanded to the Nash Building on West 133rd Street, where radiation detection techniques and instruments were also developed by Columbia physicists C.S. Wu, Bill Havens, and James Rainwater. Meanwhile, the Columbia Radiation Lab occupied Pupin floors 10-12, connected via Professor I.I. Rabi with the MIT Radiation Laboratory and the development of radar for the War [99].

In early 1945, Professor Eckert's newly established Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory at Columbia University, temporarily housed on Pupin's tenth floor, was given the task of performing temperature-pressure (shockwave) calculations for Los Alamos during the final months of A-bomb design and construction. From Herb Grosch's Computer: Bit Slices from a Life [57] (2003):

By this time Eckert and I knew that the unit of temperature in my calculations was a million degrees Kelvin, and so on. We kept the equations I was working with, and my translation into computable form (approved, with a warning, by the great Johnnie [von Neumann] on his first visit), and the starting values, in the big safe. What Marjorie [Herrick] and [machine room operator] Cliff and the others saw was a long shelf of 28 IBM plugboards, which when cycled through the various machines produced a messy and unlabelled printout from the 405 tabulator. While I bundled this up and mailed it with my own hands, registered, to von Neumann — later, to [Roy] Marshak — at the anonymous Santa Fe box number, the machine room team began to repeat the cycle. We did two a day; each predicted the temperature and pressure up to the (moving) shock wave after one more time step - a millisecond. Allowing for the fact that we did not work Sundays, that was 50,400,000 times as slow as the real atomic explosion! A Cray 2 today [1991] would be ten million times faster - and give you Saturday off besides! ... The listings I mailed to Los Alamos had no hand-written labels, but matched a labelled master copy that had been carried back by Feynman: primitive but exceedingly effective security. … Then it was August 6, and the radio and the newspapers told us about Hiroshima. We knew what we had been working on, and that tens of thousands of Japanese civilians had been incinerated. Before the moral pressures could mount, events swept us away. The war in the Pacific ended, the war in Europe ended. All our perspectives lengthened overnight — from a few months "to the end of the war," to the long reaches of peace.

The CDC Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Facility List includes the following entry:

281 - SAM Laboratories, Columbia UniversityAlso Known As: SAM Laboratories

Also Known As: Special Alloyed Materials Laboratories

Also Known As: Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratories

State: New York Location: New York City

Time Period: 1942-1947

Facility Type: Department of Energy FacilityDescription: Columbia University was already researching some of the problems involved in determining whether it was feasible for the United States to build a nuclear weapon prior to the establishment of the Manhattan Engineer District (MED). Once the MED was formed in 1942, Columbia became part of the effort to build the first atomic weapons. At that time, the Columbia effort was reorganized and designated as SAM (Special Alloy Materials or Substitute Alloy Materials) Laboratories. Buildings used as part of the SAM laboratories at Columbia included Pupin, Schermerhorn, Prentiss, Havemeyer and Nash. Work at SAM Laboratories ended in 1947 with the establishment of the AEC. Subsequent work at Columbia University focused on health effects and basic nuclear physics that were not directly related to the production of nuclear weapons

The Nash building is on the east side of Broadway at West 133rd Street, and was rented by Columbia during World War II. For more about Columbia University in World War II, see the 1939-1945 sections of the Columbia University Computing History.

Also see:

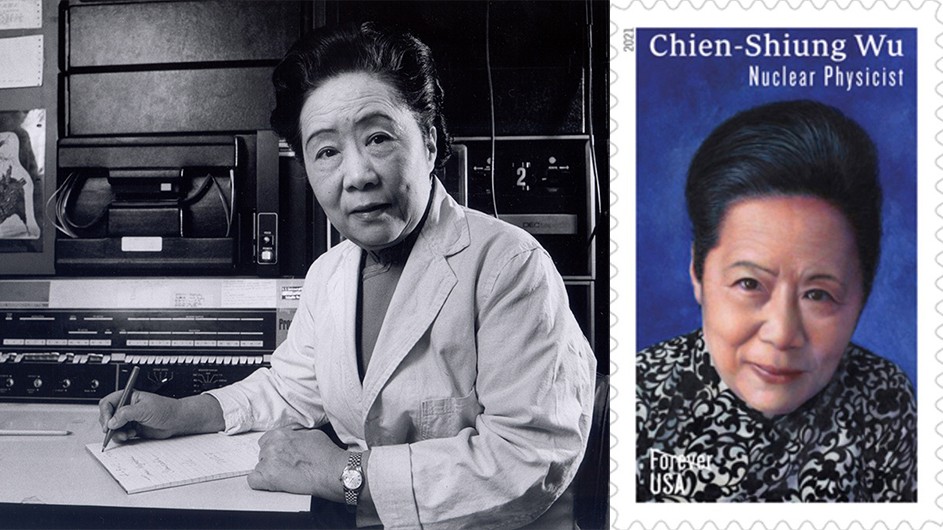

- Obituary of Chien-Shiung Wu (Columbia University Record, 21 Feb 1997).

- The Separation Of The Uranium Isotopes By Gaseous Diffusion, Chapter 10 of Atomic Energy for Military Purposes, The Official Report on the Development of the Atomic Bomb Under the Auspices of the United States Government by Henry De Wolf Smyth (July 1945).

- SAM Laboratories, Columbia University, National Occupational Safety and Health, United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Identifies Pupin, Schemerhorn [sic], Havenmeyer [sic], Nash, and Prentiss as buildings in which World War II uraniam separation research was conducted. Additional details here and here.

- Laurence Lippsett, The Manhattan Project: Columbia's wartime secret, Columbia College Today, Spring/Summer 1995, pp.18-21,45.

- Pupin Basement (Columbia Spectator, 1 Nov 2006).

- Columbia Physicist Honored With a Commemorative U.S. Postage Stamp, Columbia University website, accessed 26 February 2021.

I worked for Bill Havens and Chien-Shung Wu at the Physics Department in

Pupin Hall for a time in the late 1960s, and remember their stories about

uranium separation and the Nash building, and I met some of the other

figures from those days, including Rabi and Rainwater. I also worked for

Herb Goldstein, who had been at the MIT Radiation Lab during the war, and

who had an extensive collection of WWII memorabilia, including the complete

United States Strategic Bombing Survey, which occupied a whole bookshelf

in his office. Columbia returned to A-bomb

research in 1945 at the newly founded Thomas J. Watson Scientific

Computing Laboratory to "give all possible aid to the war" on the upper

floors of Pupin before it moved to at 612 West 116th

Street, the building that is now Casa Hispanica. See photos

here and

here. I wish I could identify the computer at left

but it doesn't match any of the likely candidates: DEC PDP-4, PDP-8, PDP-9,

PDP-11, or PDP-anything.

Chien-Shiung Wu and 2021 stamp

Translations of this page courtesy of...

| Language | Link | Date | Translator | Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusian | Беларуская | 2023/08/22 | Vladyslav Byshuk | Владислав Бишук | studycrumb.com |

| Finnish | Suomi | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | writemyessay4me.org |

| French | Français | 2023/08/25 | Kerstin Schmidt | prothesiswriter.com |

| German | Deutsch | 2023/01/02 | Valeria T. | Global Translation Services |

| German | Deutsch | 2023/08/25 | Kerstin Schmidt | writemypaper4me.org |

| Italian | Italiano | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | admission-writer.com |

| Polish | Polski | 2023/08/25 | Kerstin Schmidt | justdomyhomework.com |

| Portuguese | Português | 2024/08/05 | Rosie Bradley | MyPaperHelp |

| Russian | Русский | 2023/08/22 | Vladyslav Byshuk | Владислав Бишук | skyclinic.ua |

| Spanish | Español | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | pro-academic-writers.com |

| Ukrainian | Українська | 2023/08/22 | Vladyslav Byshuk | Владислав Бишук | studybounty.com |