The IBM Card Programmed Calculator

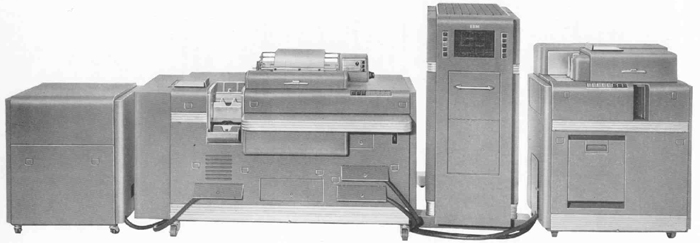

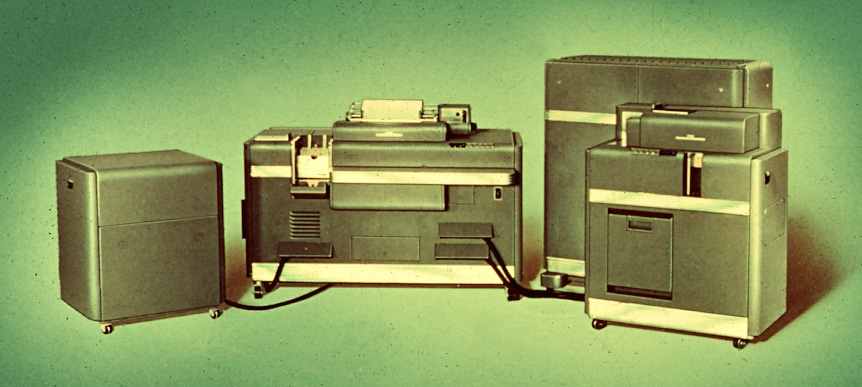

The IBM Card Programmed Electronic Calculator Model A1

Left to right: Type 941 Storage Unit, Type 412-418 Accounting Machine, Type 605 Electronic Calculator, Type 527 High-Speed Punch. Photo: IBM CPC Principles of Operation, 22-8686-3 (1954); CLICK IMAGE to magnify.

At an IBM-sponsored computation forum in 1946, and at another one in 1947,

Columbia Professor Wallace Eckert described

his Watson Lab setup in which "we have two small

relay calculators which are experimental; one is being tied in with an accounting machine and a special control box to operate as

a baby sequence calculator with instructions on punched cards" [105]

The CPC could accommodate larger programs than the 604 (or 605) by itself, by having them stored on punched cards; hence the name. In fact, there was no limit to the length of the program. Needless to say, the ability to program a calculator with a deck of cards rather than (literally) hardwiring the program onto a panel was a rather significant development. The CPC was not, however, a stored-program computer like the 650 or 701; it was an "externally programmed automatic calculator," meaning that instructions were executed directly from cards. It was possible, however, to store up to 10 instructions in memory and execute them repeatedly in a loop.

The CPC units could be configured in various combinations; e.g. zero, one, or more 941 storage units for the desired amount of memory. Here are the general specs for the five models ("Types"):

| Type | Length | Width | Weight | Amps | BTUs | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 412 | 75" | 43" | 2626 lb. | 6.0A | 5000 | 100 cards/minute, alphanumeric |

| 418 | 75" | 43" | 2553 lb. | 6.0A | 5000 | 150 cards/minute, numeric only |

| 527 | 40" | 26" | 785 lb. | 3.2A | 2190 | Calculating summary punch. |

| 605 | 53" | 33" | 1535 lb. | 33.0A | 19450 | Calculator, similar to 604. |

| 941 | 32" | 26" | 585 lb. | 1.6A | 1290 | Stores 16 10-digit signed numbers. |

While card programming was a major breakthrough, it was a bit different from

what you might think. Since the instruction field on the card referred to a

"microprogram" on the 604 or 605 plugboard,

the same deck of cards would produce entirely

different results with differently wired plugboards; thus it was not possible

to tell what a program did just by "reading" it. Within a few years, once

general-purpose stored-program computers such as the

650 and 701 became available,

programming languages such as SOAP and FORTRAN appeared that did, indeed, "say

what they did" (and vice versa!).

___________________

- Brennan [9] confirms: "...an experimental model of a fast arithmetic processor, which Eckert attached to an accounting machine. Instead of being programmed through wiring on the control panel, the machine was controlled by coded punches on cards. The result as an early form of sequence calculator that anticipated IBM's famed Card Programmed Calculator."

- Bashe [4] says the original Northrop contraption was based on a 601 but Grosch [57], who was involved in this episode (Bashe did not come to IBM until 1957), confirms it was a 603.

- Northrop might well have attended the 1946 and '47 forums. In any case, Eckert's 1946 and '47 presentations were printed in the proceedings for those years, which Northrop almost certainly received. Northrop had their own presentation on this subject printed in the 1948 Proceedings (Reference 3 below), in which they acknowledged Eckert's earlier work. Eckert's "baby sequence calculator" reference [105]: refers not to the Aberdeen machines, but to two truly custom, one-off machines built specially for Watson Lab, dubbed Virginia and Nancy.

- The IBM Card-Programmed Electronic Calculator Model A1 Using Machine Types 412-418, 605, and 941: Principles of Operation, International Business Machines: Third Edition, Form 22-8696-3 (1954).

- The Bashe [4], Pugh [40], and Grosch [57] books.

- Eckert, W.J., "Facilities of the Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory", Proceedings of the Research Forum, IBM, Endicott NY (1946), pp.75-80.

- Eckert, W.J., "The IBM Department of Pure Science and the Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory", Education Research Forum Proceedings, IBM, Endicott NY (1947)

- Fenn, George S. (Northrop Aircraft), "Programming and Using the Type 603-405 Combination Machine in the Solution of Differential Equations" in Grosch, H.R.J. (ed.), Proceedings of the Scientific Computation Forum, IBM (1948).

- Hamming, R.W., "A 101 Control Panel for Testing General Purpose CPC Cards", IBM Technical Newsletter, No.9, IBM, New York (Jan 1955), pp.53-55.

- Hurd, Cuthbert, "The IBM Card-Programmed Electronic Calculator", Proceedings, Scientific Computation Forum, IBM, New York (1949), pp.37-41.

- Krawitz, Eleanor, "The Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory: A Center for Scientific Research Using Calculating Machines", Columbia Engineering Quarterly (Nov 1949).

- MacMillan, Donald B., and Richard H. Stark, "'Floating Decimal' Calculation on the IBM Card Programmed Electronic Calculator", Mathematical Tables and Other Aids to Computation, Vol.5, No.34 (Apr 1951), pp.86-92.

- Pendery, D.W., "604 Wiring Chart for Multiply, Divide, and Square Root on the Card-Programmed Electronic Calculator", IBM Technical Newsletter, No.1, IBM, New York (1950).

- Sheldon, John W., and Liston Tatum, "The IBM Card-Programmed Electronic Calculator", Review of Electronic Digital Computers, Joint AIEE-IRE Computer Conference, American Institute of Electrical Engineers, New York (Feb 1952), pp.30-36.

- Verzuh, Frank M., "Description of THE M.I.T. CPC Board No. V, A 13- Digit Floating-Point Decimal Board", Report S-14, MIT Office of Statistical Services, Cambridge MA (25 Jun 1953), 17pp. Also similar Reports S-10 and S-14.

- Woodbury, William W., "The 603-405 Computer", Proceedings of a Second Sysmposium on Large-Scale Digital Calculating Machinery, Annals of the Computation Laboratory of Harvard University, Vol.26, Harvard University Press (1951), pp.316-320.

- IBM Scientific Computing Forum Proceedings and Technical Newsletters from the 1950s are full of articles describing CPC applications and techniques.

Also see:

IBM 402,

IBM 405,

IBM 407,

IBM 601,

IBM 602,

IBM 603,

IBM 604,

IBM 607,

IBM 608,

IBM 609,

Northrop,

Aberdeen.

And THIS GROUP PHOTO of the 1948 Computation

Forum attendees.

- Card-Programmed Electronic Calculator (CPC) (IBM history archive).

- The IBM Card-Programmed Electronic Calculator (John W. Sheldon and Liston Tatum, IEEE-IRE Computer Conference, December 1951)

- CPC Plugboards

- Kapitel 3: IBMs erste Computer (in German)

- Memoirs of George Trimble

Translations of this page courtesy of...

| Language | Link | Date | Translator | Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusian | Беларуская | 2023/08/22 | Vladyslav Byshuk | Владислав Бишук | studycrumb.com |

| Finnish | Suomi | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | https://writemyessay4me.org/ |

| French | Français | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | prothesiswriter.com |

| German | Deutsch | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | writemypaper4me.org |

| Italian | Italiano | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | https://admission-writer.com/ |

| Norwegian | Norsk (bokmål) | 2022/08/10 | Rune | Bildeler på nett |

| Polish | Polski | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | justdomyhomework.com |

| Spanish | Español | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | https://pro-academic-writers.com/ |

| Russian | Русский | 2023/08/22 | Vladyslav Byshuk | Владислав Бишук | skyclinic.ua |

| Ukrainian | Українська | 2023/08/22 | Vladyslav Byshuk | Владислав Бишук | studybounty.com |