AN ELECTRIC TABULATING SYSTEM.

BY H. HOLLERITH.

From The Quarterly, Columbia University School of Mines, Vol.X No.16 (Apr 1889), pp.238-255. In this article the author, Columbia graduate (Mines 1879) Herman Hollerith, describes the devices and methods he developed to automate the 1890 US Census; it is the basis for his 1890 Columbia Ph.D. It was scanned and converted to HTML by Frank da Cruz of Columbia University in January 2004 for the Columbia University Computing History Project. The original text was not altered in any way (unless by accident) except that words that were broken by hyphenation have been rejoined. Original page numbers are shown inline as [-xx-]. Images, footnotes, and tables are placed approximately as in the original article; click on any image to view a larger version. (Figures begin on page 247.) Updated to HTML5 and for translations, January 2019, and for fluidity in March 2020.

FEW, who have not come directly in contact with a census office, can form any adequate idea of the labor involved in the compilation of a census of 50,000,000 persons, as was the case in the last census, or of over 62,000,000, as will be the case in the census to be taken in June, 1890. The fact, however, that Congress at its last session in "An Act to provide for the taking of the eleventh and subsequent censuses," fixes the maximum cost of the next or eleventh census, exclusive of printing and engraving, at $6,400,000, will perhaps impress one with some idea of the magnitude of such an undertaking.

Although our population is constantly increasing, and although at each census more complicated combinations and greater detail are required in the various compilations, still, up to the present time, substantially the original method of compilation has been [-239-] employed; that of making tally-marks in small squares and then adding and counting such tally-marks.

While engaged in work upon the tenth census, the writer's attention was called to the methods employed in the tabulation of population statistics and the enormous expense involved. These methods were at the time described as "barbarous, some machine ought to be devised for the purpose of facilitating such tabulations. This led the writer to a thorough study of the details of the methods used, which were no doubt the most approved ever employed in compiling a census. After a careful consideration of the many problems involved and considerable experimenting on quite a large scale, the method which forms the subject of this paper is confidently offered as a means for facilitating this work.

The work of a census can be divided into two main branches: that of enumeration, and that of compilation or tabulation. In regard to the enumeration, the plan originally adopted at the tenth census, with such splendid results, will substantially be followed in the next census, and is provided for in the Act of Congress above referred to. As under the provisions of this Act the enumerators are paid according to the number of persons, farms, or manufacturing establishments enumerated, and as the rates of compensation are slightly increased, the per capita cost of the enumeration must of necessity be slightly in excess of that of the tenth census. Referring to the records of the tenth census, we find the cost of the enumeration to have been $2,095,563.32.*

An increase of population of thirty per cent. during the decade

can reasonably be assumed, so that the cost of the enumeration

at the eleventh census, at the same per capita rate, would be not

less than $2,724,232.32. Adding to this amount the cost of the

extra schedules required under the present Act of Congress and

allowing for the increased rates of compensation for the enumeration

_____________________

* The cost of the tenth census was as follows:

Enumerators $2,095,563.32 Superintendent's Office 2,385,999.50 Special Agents 625,067.29 Printing Reports 678,624.61 Total $5,785,254.72

[-240-] of farms and manufacturing establishments,* we see that an estimate of $3,000,000 is not an unreasonable one for the cost of the next enumeration.

From the data thus enumerated are compiled the various reports which form the legitimate work of a census. The expenses of the office of the Superintendent of the Tenth Census at Washington amounted to $2,385,999.50. If the same methods of compilation are to be employed in the next census, the per capita cost of compilation would, of course, remain substantially the same, so that allowing for the increased population, the expenses of this portion of the work would amount to $3,101,799.67. To this ought also be added the cost of compiling the additional data required under the present Act of Congress. If, however, the data enumerated at the next census is compiled with that fulness and completeness which it deserves, and which it ought to receive, these expenses would far exceed the above amount. As will be shown presently, many of the facts enumerated in the tenth census were not compiled at all, or if compiled were treated in so simple and elementary a manner as to leave much to be desired. On the other hand, however, the compilations of the tenth census were so vastly superior to anything that had previously been attempted that it is very likely to be inferred that the tenth census left nothing to be desired. If at the eleventh census no material improvements are adopted in the methods of tabulation, it will probably be found impossible to accomplish more than at the tenth census on account of the time and expense involved.

A census is often spoken of as a photograph of the social and economic conditions of a people. The analogy can be made, not only with reference to the results obtained, but also to the methods

Enumerators Rates of Compensation 1890

Cens.1880

Cens.For each inhabitant enumerated 2 2 For each death recorded 2 2 For each farm returned 15 10 For each manufacturing industry reported 20 15 For each soldier, sailor, etc 5 .............

[-241-] of obtaining these results. Thus the enumeration of a census corresponds with the exposure of the plate in photography, while the compilation of a census corresponds with the development of the photographic plate. Unless the photographic plate is properly exposed it is impossible to obtain a good picture, so likewise, in case of a census, a good result is impossible unless the enumeration is made properly and with sufficient detail. As the first flow of the developer brings out the prominent points of our photographic picture, so in the case of a census the first tabulations will show the main features of our population. As the development is continued, a multitude or detail appears in every part, while at the same time the prominent features are strengthened, and sharpened in definition, giving finally a picture full of life and vigor. Such would be the result of a properly compiled and digested census from a thorough enumeration. If this country is to expend $3,000,000 on the exposure of the plate, ought not the picture be properly developed?

The population schedules of the tenth census contained the following inquiries, the replies to which were capable of statistical treatment:

- Race or color: whether white, black, mulatto, Chinese, or Indian.

- Sex.

- Age.

- Relationship of each person enumerated to the head of the family.

- Civil or conjugal condition: whether single, married, widowed, or divorced.

- Whether married during the census year.

- Occupation.

- Number of months unemployed.

- Whether sick or otherwise temporarily disabled so as to be unable to attend to ordinary business or duties on the day of the enumeration; what was the sickness or disability?

- Whether blind, deaf and dumb, idiotic, insane, maimed, crippled, bedridden, or otherwise disabled.

- Whether the person attended school during the census year.

- Cannot read.

- Cannot write.

- Place of birth. [-242-] Place of birth of father.

- Place of birth of mother.

Such an enumeration as this, if made thoroughly, certainly corresponds to a fully timed exposure of our photographic plate. It would scarcely be termed under-exposed.

If it is of interest and value to know the number of males and of females in our population, of how much greater interest is it to know the number of native males and of foreign males; or again, to know the number of native white males, of foreign white males, of colored males, etc.; or still again, the combination of each one of these facts with each single year of age. All this was done in the tenth census. Many other interesting and valuable combinations were compiled, far surpassing anything of the kind that had ever before been attempted, still, on the other hand, many of the facts enumerated were never compiled at all. Thus, for example, it is to-day impossible to obtain the slightest reliable statistical information regarding the conjugal conditions of our people, though the complete data regarding this is locked up in the returns of the enumeration of the tenth census. In other words, the development was not carried far enough to bring out even this most important detail of our picture. The question why this information was not compiled was several times asked during the discussion of the present census bill in the committee of the Senate. A correct and proper answer to this inquiry would probably have been simply, "lack of funds. for a minute that the eminent statistician who planned and directed the tenth census did not fully appreciate the value of such a compilation.

To know simply the number of single, married, widowed, and divorced persons among our people would be of great value, still it would be of very much greater value to have the same information in combination with age, with sex, with race, with nativity, with occupation, or with various sub-combinations of these data. If the data regarding the relationship of each person to the head of the family were properly compiled, in combination with various other data, a vast amount of valuable information would be obtained. So again, if the number of months unemployed were properly enumerated and compiled with reference to age, to occupation, etc., much information might be obtained of great [-243-] value to the student of the economic problems affecting our wage-earners.

One more illustration will be given. We have in a census, besides the data relating to our living population, records regarding the deaths during the previous year. In both cases we have the information regarding age and occupation. It the living population were tabulated by combinations of age and occupation, and likewise the deaths by ages and occupations, we would then have data from which some reliable inferences might be drawn regarding the effects of various occupations upon length of life. It might even be possible to construct life tables for the various occupations as we now do for the different States and cities. Such information would be of service in relation to life insurance and other problems. Again. it would point out any needed reforms regarding the sanitary conditions and surroundings of any occupation. This is a field of statistical investigation which is as yet almost wholly unexplored.

In this connection it may perhaps be proper to quote from a letter addressed to the writer, in reply to certain inquiries, by General Francis A. Walker, the well-known Superintendent of the Tenth Census:

"In the census of a country so populous as the United States the work of tabulation might be carried on almost literally without limit, and yet not cease to obtain new facts and combinations of facts of political, social, and economic significance.

"With such a field before the statistician, it is purely a question of time and money where he shall stop. Generally speaking, he cannot do less than has been done before in the treatment of the same subject. Generally speaking, also, he will desire to go somewhat beyond his predecessors, and introduce some new features to interest and instruct his own constituency, so that there is a constant tendency to make the statistical treatment of similar material successively more and more complex. It will even frequently happen that these later refinements in the statistics of a country are of greater economic significance than some of the earlier and more elementary grouping of facts."

No one is more competent to speak authoritatively on this question than General Walker, and certainly no one's opinion is more worthy of consideration.

Irrespective of the wishes and desires of those who are in charge [-244-] of our various statistical inquiries, we often find in this country that public opinion needs and demands certain statistical information. Thus in the present Act of Congress while the main points are left discretionary with the Secretary of the Interior, under whose direction the census is taken, still on certain points direct instructions are given. For example, it is provided that the colored population be enumerated and tabulated with reference to the distinctions of blacks, mulattoes, quadroons, and octoroons. In the census of 1860 the population was compiled under 14 age groups, in 1870 the ages were tallied under 25 groups, while in 1880 the census office, in compliance with numerous requests from many different sources, tabulated the population according to single years of age, making in all over 100 specifications. Thus we see that each year the problem of compiling a census becomes a more difficult one.

Heretofore in census and similar compilations essentially one of two methods has been followed. Either the records have been preserved in their proper relations, and the information drawn off by tallying first one grouping of facts and then the next, or the records have been written upon cards or slips, which are first sorted and counted according to one grouping of facts and then according to the next.

To form some idea of the questions involved in the first plan, let us assume that the record relating to each person at the next census be written in a line across a strip of paper, and that such lines are exactly one-half inch apart, it would then take a strip of paper over 500 miles long to contain such records. These must be gone over, again and again, until all the desired combinations have been obtained. This is practically the method followed in compiling the tenth census. On the other hand, if written cards are to be used the prospect is hardly more encouraging. One hundred comparatively thin cards will form a stack over an inch high.

In the next census, therefore, if such cards are to be used it will require a stack over ten miles high. Imagine for a moment the trouble and confusion which would be caused by a few such cards becoming misplaced. This method of individual cards was employed in the census of Massachusetts for 1885. The 2,000,000 cards there used weighed about 14 tons. Were the same cards to be used in the next United States census it would require about 450 tons of such cards.

[-245-] In place of these methods it is suggested that the work be done so far as possible by mechanical means. In order to accomplish this the records must be put in such shape that a machine could read them. This is most readily done by punching holes in cards or strips of paper, which perforations can then be used to control circuits through electro-magnets operating counters, or sorting mechanism, or both combined.

Record-cards of suitable size are used, the surfaces of which are divided into quarter-inch squares, each square being assigned a particular value or designation. If, for example, a record of sex is to be made, two squares, designated respectively M and F, are used, and, according as the record relates to a male or a female, the corresponding square is punched. These holes may be punched with any ordinary ticket-punch, cutting a round hole, about three-sixteenths of an inch in diameter. In similar manner other data, such as relate to conjugal condition, to illiteracy, etc., is recorded. It is often found, however, that the data must be recorded with such detail of specification that it would be impracticable to use a separate space for each specification. In such cases recourse is had to combinations of two or more holes to designate each specification. For example, if it is desired to record each single year of age, twenty spaces are used, divided into two sets of ten each, designated, respectively, from 0 to 9. One set of ten spaces is used to record the tens of years of age, while the other set is used to record the units of years of age. Thus, twelve years would be recorded by punching I in the first set, and 2 in the second; while 21 years would be recorded by punching 2 in the first set, and 1 in the second set. Occupations may be arranged into arbitrary groups, each such group being designated, for example, by a capital letter, and each specific occupation of that group by a small letter. Thus, Aa would designate one occupation, Ab another, etc. If desired, combinations of two or more letters of the same set may be used. Thus, AB can be used to designate one occupation, AC another I BC another, etc. With such an arrangement, the initial letter may be used to designate groups of occupation as before. In this way it is apparent that a very small card will suffice for an elaborate record. For the work of a census, a card 3" × 5½" would be sufficient to answer all ordinary purposes. The cards are preferably made of as thin manilla stock as will be convenient to handle.

If printed cards are used, the punching may be done with ordinary ticket-punches; [-246-] more satisfactory results, however, can be obtained with punches designed especially for this work, as will be presently described.

In a census the enumerator's district forms the statistical unit of area, and a suitable combination is arranged to designate each such district. A card is punched with the corresponding combination for each person in such enumeration districts, and the cards of each district are then numbered consecutively, in a suitable numbering machine, to correspond with numbers assigned to the individual records on the enumerator's returns. This combination of holes, and this number, will serve to identify any card. Should any card become misplaced, it is readily detected among a number of cards by the fact that one or more of these holes will not correspond with the holes in the balance of the cards. By means of a suitable wire or needle a stack of a thousand or more cards can be tested in a few seconds, and any misplaced cards detected. When it is remembered that in a census millions of cards must constantly be handled, the importance of this consideration is appreciated. With ordinary written cards it would be practically impossible to detect misplaced cards, and a few such misplaced cards would cause almost endless confusion.

As the combination of holes used for designating the enumerator's district are the same for all the cards of that district, a special machine is arranged for punching these holes. This machine is provided with a number of interchangeable punches, which are placed according to the combination it is desired to punch. Five or six cards are then placed in the punch against suitable stops, and by means of a lever the corresponding holes are punched through these cards at one operation.

The individual records are now transcribed to the corresponding

cards by punching according to a pre-arranged scheme as described

above. For this purpose what may be known as a keyboard-punch

is arranged, in which the card is held fixed in a frame, while the

punch is moved over the card in any direction by means of a projecting

lever provided with a suitable knob or handle. Below the

knob is a keyboard provided with holes lettered and numbered

according to the diagram of the card, and so arranged that when

a pin projecting below the knob is over any hole, the punch is over

the corresponding space of the card. If the pin is depressed into

any hole of the keyboard, the punch is operated and the corresponding

one corner, however, being cut off to properly locate the card in subsequent

operations.

[-247-]

space of the card is punched. With such a keyboard-punch

it is, of course, apparent that a perfectly blank card may be used,

one corner, however, being cut off to properly locate the card in subsequent

operations.

To read such a punched record card, it is only necessary to [-248-] place it over a printed form, preferably of a different color, when the complete record shows directly through the perforations.

Heretofore, reference has only been made to the compilation of a census, but these methods are equally applicable to many other forms of statistical compilations, as, for example, the various forms of vital statistics. Fig. 1, for example, represents the diagram of the card as at present used in the office of the Surgeon-General U.S.A., for compiling the army health statistics. The data relating to the month, the post, the division, and the region to which the record relates, is recorded by punching a hole in each of the divisions across the end of the card by means of the machine with interchangeable punches as before described. This portion of the record corresponds almost exactly with the record for the enumeration district of a census. The individual record is then transcribed to the card by punching in the remaining spaces with a keyboard-punch as before described.

Such a card allows a complete record, including the

following data, for each individual; rank, arm of service, age, race,

nationality, length of service, length of residence at the particular post,

whether the disease was contracted in the line of duty or not, whether

admitted to sick report during the month or during a previous month, the

source of admission, the disposition of the case, or whether remaining under

treatment, the place of treatment, the disease or injury for which treated,

and finally the number of days treated. Between 40,000 and 50,000 such

records are received

[-249-]

annually, and from these are compiled the various health statistics

pertaining to our army.

Such a card allows a complete record, including the

following data, for each individual; rank, arm of service, age, race,

nationality, length of service, length of residence at the particular post,

whether the disease was contracted in the line of duty or not, whether

admitted to sick report during the month or during a previous month, the

source of admission, the disposition of the case, or whether remaining under

treatment, the place of treatment, the disease or injury for which treated,

and finally the number of days treated. Between 40,000 and 50,000 such

records are received

[-249-]

annually, and from these are compiled the various health statistics

pertaining to our army.

A card has just been arranged for the Board of Health of New

York City to be used in compiling the mortality statistics of that

city. The record for each death occurring in the City of New

York, as obtained from the physicians' certificates, is transcribed

to such a card by punching as before described. This card allows

for recording the following data: sex, age, race, conjugal condition,

occupation, birthplace, birthplace of parents, length of residence

in the city; the ward in which the death occurred, the sanitary

subdivision of such ward, the nature of the residence in which the

death occurred, whether a tenement, dwelling, hotel, public

institution, etc., and finally the cause of death. In the city of New

York about 40,000 deaths are recorded annually.

A card has just been arranged for the Board of Health of New

York City to be used in compiling the mortality statistics of that

city. The record for each death occurring in the City of New

York, as obtained from the physicians' certificates, is transcribed

to such a card by punching as before described. This card allows

for recording the following data: sex, age, race, conjugal condition,

occupation, birthplace, birthplace of parents, length of residence

in the city; the ward in which the death occurred, the sanitary

subdivision of such ward, the nature of the residence in which the

death occurred, whether a tenement, dwelling, hotel, public

institution, etc., and finally the cause of death. In the city of New

York about 40,000 deaths are recorded annually.

These illustrations will serve to show how readily a card can be arranged to record almost any desired grouping of facts.

With a little practice great expertness is secured in making such transcriptions, and a record can thus be transcribed much more readily than by writing, even if considerable provision is made for facilitating the writing by the use of abbreviations.

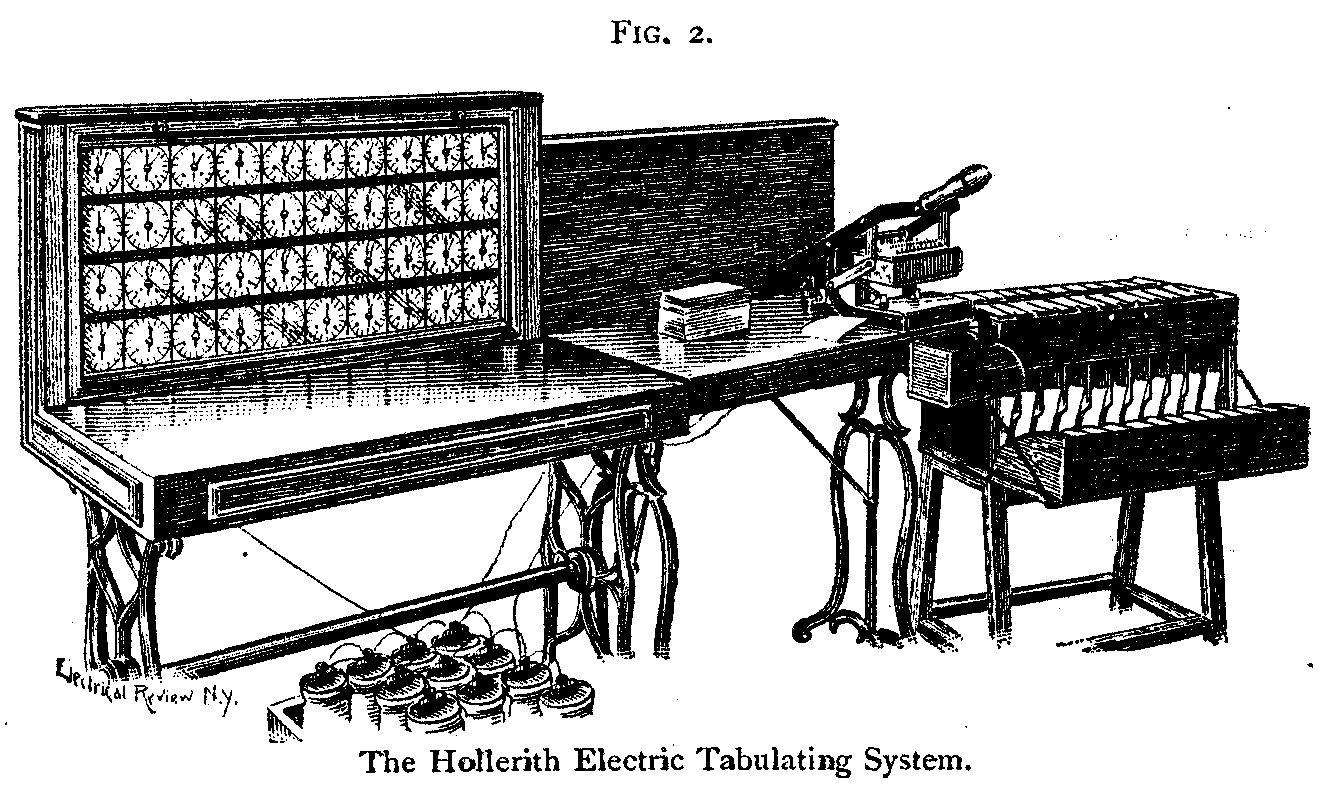

From the punched record cards it next becomes necessary to

[-250-]

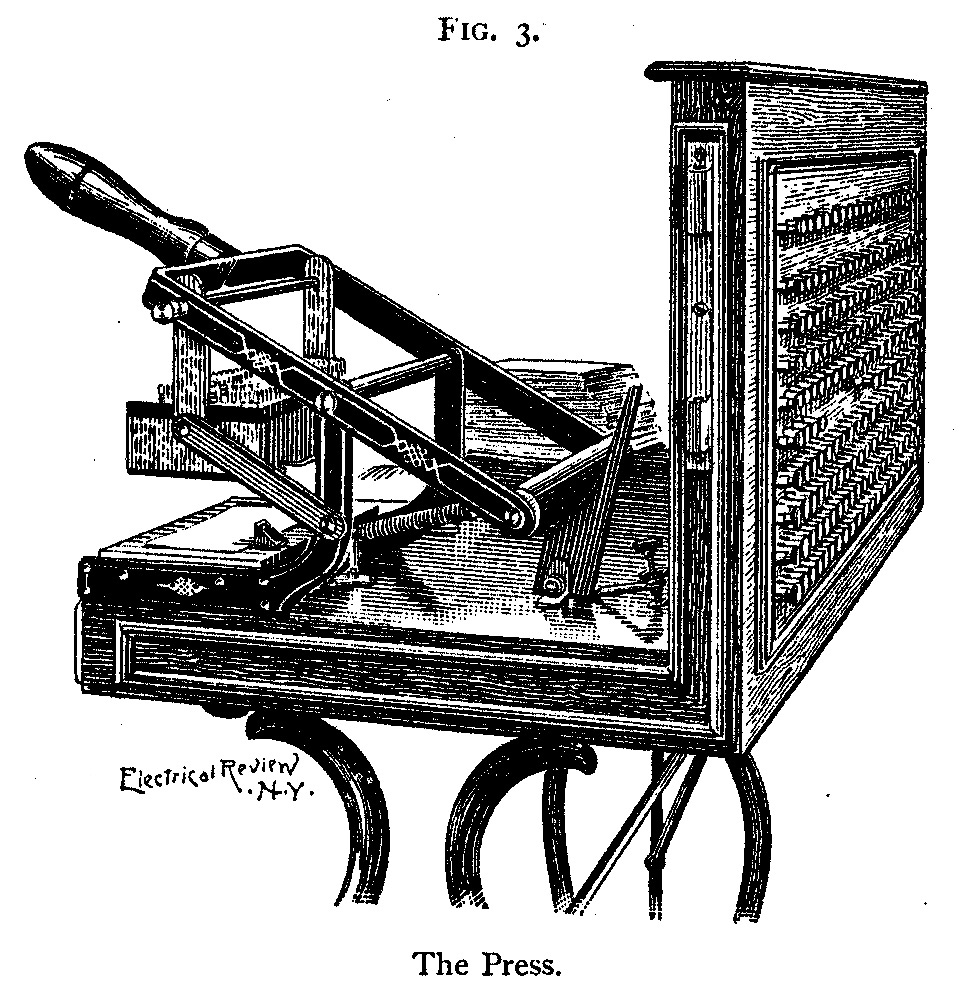

compile the desired statistics. For this purpose the apparatus

shown in Figs. 2 to 8 is used. The press or circuit-closing device,

shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, consists of a hard rubber bed plate,

as shown in section in Fig. 4, provided with suitable stops or

gauges against which the record-cards can be placed. This hard

rubber plate is provided with a number of holes or cups corresponding

in number and relative position with the centres of the

spaces of the card. An iron wire nail is securely driven through

a hole in the bottom of each cup, and a wire, connecting at its

other end with a binding-post on the back of the press frame, is

securely held under the head of each nail. Each cup is partly

filled with mercury, which, through the nail and wire, is thus in

electrical connection with the corresponding binding-post. Above

the hard rubber plate is a reciprocating box provided with a

number of projecting spring-actuated points, corresponding in

number and arrangement with the centres of the mercury cups.

The construction and arrangement of these pins is shown in Fig.

4. If a card is placed on the rubber plate against the stops it is

of course apparent that, when the box is brought down by the

handle, the pins will all be pressed back, excepting such as correspond

[-251-]

with the punched spaces of the card which project into the

mercury, and are thus in electrical connection with the corresponding

binding-posts on back of the press frame.

From the punched record cards it next becomes necessary to

[-250-]

compile the desired statistics. For this purpose the apparatus

shown in Figs. 2 to 8 is used. The press or circuit-closing device,

shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, consists of a hard rubber bed plate,

as shown in section in Fig. 4, provided with suitable stops or

gauges against which the record-cards can be placed. This hard

rubber plate is provided with a number of holes or cups corresponding

in number and relative position with the centres of the

spaces of the card. An iron wire nail is securely driven through

a hole in the bottom of each cup, and a wire, connecting at its

other end with a binding-post on the back of the press frame, is

securely held under the head of each nail. Each cup is partly

filled with mercury, which, through the nail and wire, is thus in

electrical connection with the corresponding binding-post. Above

the hard rubber plate is a reciprocating box provided with a

number of projecting spring-actuated points, corresponding in

number and arrangement with the centres of the mercury cups.

The construction and arrangement of these pins is shown in Fig.

4. If a card is placed on the rubber plate against the stops it is

of course apparent that, when the box is brought down by the

handle, the pins will all be pressed back, excepting such as correspond

[-251-]

with the punched spaces of the card which project into the

mercury, and are thus in electrical connection with the corresponding

binding-posts on back of the press frame.

A number of mechanical counters are arranged in a suitable

frame, as show in Fig. 5. The face of each counter is three

inches square, and is provided with a dial divided into 100 parts

and two hands, one counting units the other hundreds. The

counter consists essentially of an electro-magnet, the armature of

which is so arranged that each time it is attracted by closing the

circuit it registers one. A suitable carrying device is arranged so

that at each complete revolution of the unit hand the hundred

hand registers one, each counter thus registering or counting to

one hundred hundred, or 10,000, which will be found sufficient for

all ordinary statistical purposes. The counters are so arranged

that they can readily be reset at 0, and all are removable and

interchangeable, the mere placing of the counter in position in

the frame making the necessary electrical connections through the

magnet.

A number of mechanical counters are arranged in a suitable

frame, as show in Fig. 5. The face of each counter is three

inches square, and is provided with a dial divided into 100 parts

and two hands, one counting units the other hundreds. The

counter consists essentially of an electro-magnet, the armature of

which is so arranged that each time it is attracted by closing the

circuit it registers one. A suitable carrying device is arranged so

that at each complete revolution of the unit hand the hundred

hand registers one, each counter thus registering or counting to

one hundred hundred, or 10,000, which will be found sufficient for

all ordinary statistical purposes. The counters are so arranged

that they can readily be reset at 0, and all are removable and

interchangeable, the mere placing of the counter in position in

the frame making the necessary electrical connections through the

magnet.

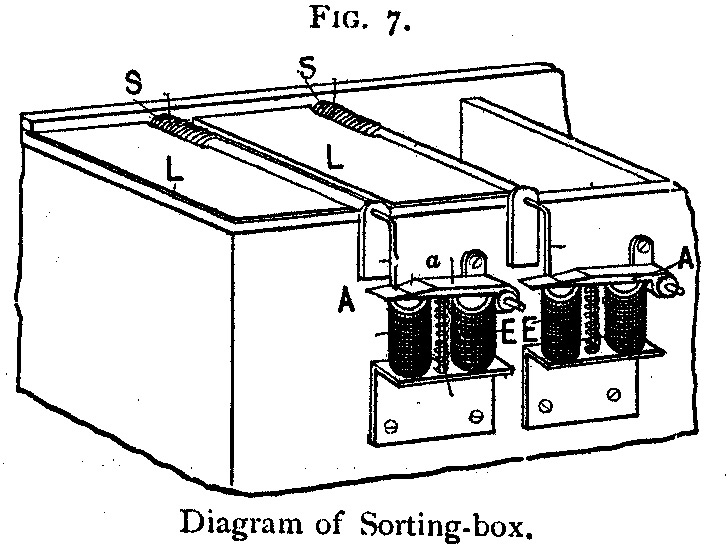

For the purpose of sorting the cards according to any group of

[-252-]

statistical items or combinations of two or more of such items, the

sorting-box, shown in Fig. 6, is used. This consists of a box

suitably divided into compartments, each one of which is closed

by a lid. Each lid, L, as shown in Fig. 7, is held closed against

the tension of the spring, S, by the catch, a, in the armature, A.

If a circuit is closed through the magnet, E, the armature, A, is

attracted, thus releasing the lid, L, which is opened by the springs,

and remains open until again closed by hand.

For the purpose of sorting the cards according to any group of

[-252-]

statistical items or combinations of two or more of such items, the

sorting-box, shown in Fig. 6, is used. This consists of a box

suitably divided into compartments, each one of which is closed

by a lid. Each lid, L, as shown in Fig. 7, is held closed against

the tension of the spring, S, by the catch, a, in the armature, A.

If a circuit is closed through the magnet, E, the armature, A, is

attracted, thus releasing the lid, L, which is opened by the springs,

and remains open until again closed by hand.

As the cards are punched they are arranged by enumerators' districts, which form our unit of area. The first compilation that would be desired would be to obtain the statistics for each enumeration district according to some few condensed groupings of facts. Thus it might be desired to know the number of males and of females, of native born and of foreign born, of whites and of colored, of single, married, and widowed, the number at each of centre groups of ages, etc., in each enumeration district. In order to obtain such statistics the corresponding binding-posts on the back of the press frame are connected, by means of suitable piece of covered wire, with the binding-posts of the counters upon which it is desired to register the corresponding facts. A proper battery being arranged in circuit, it is apparent that if a card is placed on [-253-] the hard rubber bed plate, and the box of the press brought down upon the card, the pins corresponding with the punched spaces will close the circuit through the magnets of the corresponding counters which thus register one each. If the counters are first set at 0, and the cards of the given enumeration district then passed through the press one by one, the number of males and of females, of whites and of colored, etc., will be indicated on the corresponding counters.

If it is desired to count on the counters directly, combinations

of two or more items, small relays are used to control secondary

circuits through the counters. If, for example, it is desired to

know the number of native white males, of native white females,

of foreign white males, of foreign white females, of colored males.

and of colored females; these being combinations of sex, race, and

nativity, ordinary relays are arranged as shown in the diagram,

Fig. 8, the magnets of which are connected with the press as indicated.

If a card punched for native white, and male is placed in

the press, the corresponding relays are actuated, which close a

secondary circuit through the counter magnet, native white male,

thus registering one on the corresponding counter.

If it is desired to count on the counters directly, combinations

of two or more items, small relays are used to control secondary

circuits through the counters. If, for example, it is desired to

know the number of native white males, of native white females,

of foreign white males, of foreign white females, of colored males.

and of colored females; these being combinations of sex, race, and

nativity, ordinary relays are arranged as shown in the diagram,

Fig. 8, the magnets of which are connected with the press as indicated.

If a card punched for native white, and male is placed in

the press, the corresponding relays are actuated, which close a

secondary circuit through the counter magnet, native white male,

thus registering one on the corresponding counter.

By a suitable arrangement of relays any possible combination of the data recorded on the cards may be counted. When it is desired to count more complicated combinations, however, special relays with multiple contact points are employed.

If it is desired to assort or distribute the cards according to any desired item or combination of items recorded on the card, it is only necessary to connect the magnets of the sorting-box in exactly the same manner as has been described for the counters. When a card is then placed in the press, one of the lids of the sorting-box, according to the data recorded on the card, will open. The [-254-] card is deposited in the open compartment of the sorting-box and the lid closed with the right hand, while at the same time the next card is placed in position in the press with the left hand.

It is, of course, apparent that any number of items or combinations of items can be counted. The number of such items or combinations, which can be counted at any one time, being limited only by the number of counters, while at the same time the cards are sorted according to any desired set of statistical facts. In a census the cards as they come from the punching machines would, of course, be arranged according to enumeration districts.

Each districts could then be run through the press, and such facts

as it is desired to know in relation to this unit of area could be

counted on the counters, while the cards are at the same time assorted

according to some other set of facts, arranging them in

convenient form for further tabulations. In this manner, by the

arrangement of a judicious "scheme," it will be found that a most

elaborate compilation may be effected with but a few handlings of

the cards.

Each districts could then be run through the press, and such facts

as it is desired to know in relation to this unit of area could be

counted on the counters, while the cards are at the same time assorted

according to some other set of facts, arranging them in

convenient form for further tabulations. In this manner, by the

arrangement of a judicious "scheme," it will be found that a most

elaborate compilation may be effected with but a few handlings of

the cards.

Two of the most important elements, in almost all statistical compilations, are "time which results could be obtained with the present method, in a census, for example, would be dependent upon: 1st, the rate at which a clerk could punch the record-cards, and, 2d, the number of clerks employed upon this part of the work. The first can readily be determined by experiment, when the second becomes merely [-255-] a simple arithmetical computation. The work of counting or tabulating on the machines can be so arranged that, within a few hours after the last card is punched, the first set of tables, including condensed grouping of all the leading statistical facts, would be complete. The rapidity with which subsequent tables could be published would depend merely upon the number of machines employed.

In regard to accuracy, it is apparent that the processes of counting and sorting, being purely mechanical, can be arranged, with such checks, that an error is practically impossible. The one possible source of error is in the punching of the cards. If proper precautions are here taken, a census practically free from errors of compilation could be obtained. Even in this respect the present method would have manifest advantages. A card wrongly punched could involve an error of only a single unit, while by all previous methods single errors involving an error in the result of tens, of hundreds, of thousands, or even more, are possible.

It is firmly believed that in regard to cost, time and accuracy, this method would possess very great advantages in doing the work that has heretofore been done, but this is believed to be insignificant in comparison with the fact that a thorough compilation would be possible, within reasonable limits of cost, while such compilation is practically impossible, by the ordinary methods, on account of the enormous expense involved.

Translations of this page courtesy of...

| Language | Link | Date | Translator | Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian | Shqip | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | https://admission-writer.com/ |

| Bosnian | Bosanski | 2019/02/06 | Amina Dugalić | the-sciences.com |

| Danish | Dansk | 2021/08/11 | Peter Torman | Hvem eier bilen |

| Finnish | Suomi | 2019/01/14 | Marie Stefanova | Thomas Bata University, Zlin, Poland |

| French | Français | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | prothesiswriter.com |

| German | Deutsch | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | writemypaper4me.org |

| Hungarian | Magyar | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | https://writemyessay4me.org/ |

| Italian | Italiano | 2021/09/03 | David Philips | Coupontoaster |

| Italian | Italiano | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | pro-academic-writers.com |

| Macedonian | Mакедонски | 2020/09/24 | Katerina Nestiv | Екатерина Нестив | Sciencevobe.com |

| Norwegian (Bokmål) | Norsk | 2021/04/19 | Simen Gundersen | Finn det rette lånet |

| Norwegian (Nynorsk) | Norsk | 2021/08/11 | Stian Skyelbred | Lånepenger.no |

| Polish | Polski | 2023/08/31 | Kerstin Schmidt | justdomyhomework.com |

| Romanian | Română | 2019/05/17 | (anonymous) | Essay Writing Services |

| Sami | Sami | 2021/10/07 | Inga Kvive | Beste forbrukslån |

| Swedish | Swedish | 2022/08/16 | Cecilie Brekgård | Kredittkortisten |

| Spanish | Español | 2020/03/17 | Manuel Gómez | Native Casinos for Canadians |