The development of the enclosed superstadium is a

major phenomenon in the recent history of American culture and technology.

Since the Houston Astrodome's opening in 1965 marked the birth

of the superstadium (figure 1), these unprecedented buildings

have multiplied the profits of major league sports teams by bringing

games indoors - making baseball rain delays obsolete and December

football games comfortable. Superstadiums serve as giant television

studios for broadcasting the events they house, and their luxury

skyboxes bring surrogate living rooms and even corporate boardrooms

into the modern arena. Revenues from these luxury boxes and from

season-long television broadcast contracts have enriched the superstadiums'

major league tenants, but these structures rarely make money for

the cities that build and maintain them.

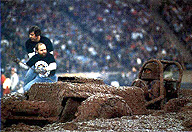

This is true in spite

of the fact that controlled climates and huge projection screens

allow these domes to host a wide variety of spectacles, from monster-truck

races to political conventions to superbowls (figure 2).

The development of the enclosed superstadium is a

major phenomenon in the recent history of American culture and technology.

Since the Houston Astrodome's opening in 1965 marked the birth

of the superstadium (figure 1), these unprecedented buildings

have multiplied the profits of major league sports teams by bringing

games indoors - making baseball rain delays obsolete and December

football games comfortable. Superstadiums serve as giant television

studios for broadcasting the events they house, and their luxury

skyboxes bring surrogate living rooms and even corporate boardrooms

into the modern arena. Revenues from these luxury boxes and from

season-long television broadcast contracts have enriched the superstadiums'

major league tenants, but these structures rarely make money for

the cities that build and maintain them.

This is true in spite

of the fact that controlled climates and huge projection screens

allow these domes to host a wide variety of spectacles, from monster-truck

races to political conventions to superbowls (figure 2).

Superstadiums have not only changed sports spectating in America

but have also transformed the cities in which they stand. Constructing

a superstadium is a major civic investment that makes a profound

impact on a city's fabric, altering circulation systems, parking

demands and neighborhood scales. Such effects make superstadiums

lighting rods for hotly contested political debates in cities

that contemplate building one, as are many American cities today.

The Houston Astrodome, the Minneapolis Metrodome and the Superdome

in Atlanta provide three early case studies of how cities have

dealt with these unwieldy forms.

Superstadiums have not only changed sports spectating in America

but have also transformed the cities in which they stand. Constructing

a superstadium is a major civic investment that makes a profound

impact on a city's fabric, altering circulation systems, parking

demands and neighborhood scales. Such effects make superstadiums

lighting rods for hotly contested political debates in cities

that contemplate building one, as are many American cities today.

The Houston Astrodome, the Minneapolis Metrodome and the Superdome

in Atlanta provide three early case studies of how cities have

dealt with these unwieldy forms.

America's Superstadiums are predominately covered by cable-stiffened pneumatic roofs or tensegrity domes, both invented since World War II. These new structural types were first erected to enclose World Exposition and Olympic buildings. Exposition and Olympic sponsors' need for economic longspan roofs and their openness to experimentation helped inspire the design of the first large pneumatic dome at the U.S. Pavilion at Expo 70 in Osaka, and the first tensegrity dome over the Fencing and Gymnastics Arenas at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. The relative economy of both roof forms helped ensure their quick adaptation for use in America's Superstadiums (figure 3, Minneapolis Metrodome, figure 4 Atlanta Georgia Dome). The U.S. Pavilion, for example, weighed less than one fifth that of traditionally constructed domes of similar size such as the Houston Astrodome, and cost much less per square foot.

The history of the inception of these new structural types illustrates

an extraordinary confluence of engineering brilliance and technology

transfer. The theoretical groundwork for tensegrity domes was

laid by R. Buckminster Fuller -- the creator of the geodesic dome

-- but the first successfully built, large-scale tensegrity structure

was designed by David Geiger, the inventor of the cable-stiffened

pneumatic dome and the structural engineer of the U.S. Pavilion.

Pneumatic and tensegrity domes owe their existence in part to

recent technological developments in unrelated disciplines, and

are prime examples of technological adaptation. Both types of

domes rely on advances in computer hardware and the science of

numerical methods that make predicting their structural performance

possible; both also employ fiberglass fabric developed for NASA

and coatings first used by the space program.

The history of the inception of these new structural types illustrates

an extraordinary confluence of engineering brilliance and technology

transfer. The theoretical groundwork for tensegrity domes was

laid by R. Buckminster Fuller -- the creator of the geodesic dome

-- but the first successfully built, large-scale tensegrity structure

was designed by David Geiger, the inventor of the cable-stiffened

pneumatic dome and the structural engineer of the U.S. Pavilion.

Pneumatic and tensegrity domes owe their existence in part to

recent technological developments in unrelated disciplines, and

are prime examples of technological adaptation. Both types of

domes rely on advances in computer hardware and the science of

numerical methods that make predicting their structural performance

possible; both also employ fiberglass fabric developed for NASA

and coatings first used by the space program.Housing the Spectacle traces the advent and evolution of America's extraordinary Superstadiums. The exhibition explores the confluence of cultural desires, economic dictates, and technological advances that propelled the evolution of domed superstadiums from heavy ribbed steel domes, through pneumatic cable-stiffened structures, to tensegrity roofs. Case studies of five domes -- the 1965 Houston Astrodome, the 1970 U.S. Pavilion at Expo 70 in Osaka, the 1981 Minneapolis Metrodome, the 1988 Seoul Olympic Fencing and Gymnastics Arenas and the 1992 Georgia Dome -- illustrate this evolution and the forces that shaped it.

Housing the Spectacle Main Menu

Housing the Spectacle Main Menu