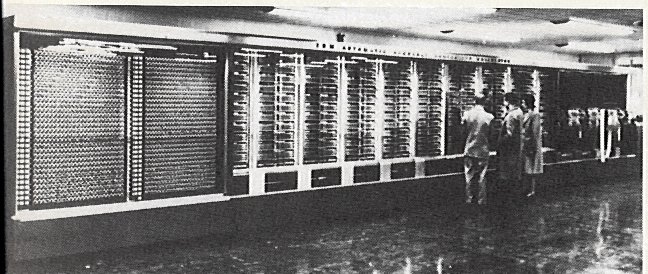

The IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator

The near-complete "Harvard machine" in IBM's North Street Laboratory, prior to delivery, November 1943 [4].

A 1945 Columbia University news release [23] cites "cooperation with Harvard University in the development of the ASCC". Perhaps it overstates the case, but the claim is bolstered by a report in Brennan [9] of Aiken's 1938 visit to Wallace Eckert's Astronomical Computing Laboratory, as well as by a footnote in Tim Bergin's Fifty Years of Army Computing [71] citing:

- Williams, Michael R., A History of Computing Technology, Second Edition, IEEE Press, Los Alamitos, CA (1997), pp.154-186.

- Lee, J.A.N.. Computer Pioneers, IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos, CA (1995), pp.51-64.

to back up its statement that Aiken was "knowledgeable of the work done at the Watson Astronomical Computing Bureau at Columbia by Wallace Eckert." The Smart Computing Encyclopedia on the Web (June 2004) contains the following paragraph in its entry on IBM engineer Clair D. Lake:

In the 1930s, Lake worked with Columbia University's Wallace Eckert at the Thomas J. Watson Astronomical Computing Bureau to build an electromagnetic calculator, which used punched cards to perform high-speed, complex mathematical calculations in the study of astronomy. News of the device spread, and Howard H. Aiken, a Harvard doctoral student in physics, met with Eckert and Lake. Aiken wanted to make a calculator that could retain mathematical rules in its memory and not require reprogramming for each new set of problems. In 1938, Watson agreed to finance the project, and the computer was built at IBM's Endicott, N.Y., facility, where Aiken collaborated with Lake and his engineering staff, namely James Bryce, Francis Hamilton, and Benjamin Durfee.

The Mark I was disassembled in 1959, but portions of it are displayed in the Science Center as part of the Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Other sections of the original machine were transferred to IBM and the Smithsonian Institution.[6].

- International Business Machines Corporation, IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, IBM, New York (1945), 6pp.

- Aiken, Howard H. and Grace M. Hopper, "The Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator", Electrical Engineering, Vol.65 No.8-9, pp.384-391 (Aug 1946); No.10, pp.449-454 (Oct 1946); No.11, pp.522-528 (Nov 1946).

- Comrie, L.J., "Babbage's Dream Comes True", Nature, Vol.159 (1946), pp.567-568.

- Harvard Computation Laboratory, A Manual of Operation for the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, The Annals of the Computation Laboratory of Harvard University, Vol.1, Harvard University Press (1946), 561pp.

- Bloch, Richard M., "Mark I Calculator", Proceedings of a Symposium on Large-Scale Digital Calculating Machinery, The Annals of the Computation Laboratory of Harvard University, Vol.16 (1948), pp.23-30.

- Harvard Mark I, Wikipedia, accessed 29 March 2021.

- ASCC Intro (IBM)

- ASCC Reference Room (IBM)

- Howard Hathaway Aiken - The Life of a Computer Pioneer (The Computer Museum Report #12, Spring 1985)

- William Asprey Interview with John McPherson (IEEE History Center, April-May 1992)

- Grosch, Herb, Computer: Bit Slices from a Life, Third Edition, 2003 (in manuscript); search for "Aiken".